Summary of observing raspberries for older preschoolers for Raspberry Jam Day

Tatiana Goryacheva

Summary of observing raspberries for older preschoolers for Raspberry Jam Day

Goal: expanding preschoolers’ understanding of bushes and berries.

Tasks:

- consolidate children’s existing knowledge about berries and shrubs;

- to arouse children’s interest in artistic expression;

- learn to understand the content of the riddle and the meaning of the saying;

– expand and activate vocabulary;

-develop children’s cognitive activity in the process of observation;

-develop the ability to compare, analyze, generalize, establish cause-and-effect relationships,

– develop the ability to see the beauty of nature.

- to cultivate an emotional and value-based attitude towards the world around us;

- cultivate a caring attitude towards nature.

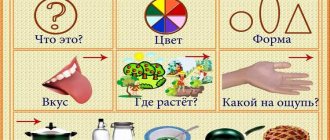

Preliminary work: conversation about the holiday Raspberry Jam Day, examination of illustrations on the topic “Berries”, “Shrubs”, children’s stories from personal experience “How I went to the forest to pick berries”.

Progress of observation

The teacher asks the children to guess the riddle:

Red beads hang

They're looking at us from the bushes,

Love these beads very much

Children, birds and bears.

Educator: Well done! Do you like raspberries? (Answers)

Where do raspberries grow?

Children: In the forest!

Educator: Yes, raspberries grow in the forest. Have you been to the forest? Have you seen how it grows, just like strawberries? Remember, we watched the berries, they grow on small branches, very close to the ground.

Educator: Let's look at the bushes, just be careful - raspberry bushes are very prickly, you can get hurt. Remember the Russian proverb about picking berries -

Children: The berry is sweet, but it’s hard to pick.

Educator: Picking raspberries is difficult not only because the bushes are prickly, but also because the berries are very soft and juicy. I squeezed it a little harder. It is better to put such a berry in your mouth, and not in the box. (Invites children to try to pick a berry)

Berries (story)

It was a hot, windless day in June. The leaves in the forest are juicy, thick and green, only here and there yellowed birch and linden leaves are torn off. The rosehip bushes are showered with fragrant flowers, the forest meadows are full of honey-colored clover, the rye is thick, tall, dark and agitated, half full, the corncrakes are calling to each other in the grasslands, the quails are wheezing and clicking in the oats and ryes, the nightingale in the forest only occasionally kneels and will fall silent, the dry heat will bake. Along the roads, dry dust lies motionless like a finger and rises in a thick cloud, carried away to the right and left by an occasional weak breath.

The peasants are finishing the buildings, hauling manure, the cattle are starving on the dried-up fallow, awaiting the harvest. Cows and calves squawk with their hooked tails raised and run from the shepherds from the stall. The guys guard the horses along the roads and edges. Women carry bags of grass from the forest, girls and girls race each other, crawl between the bushes in the felled forest, pick berries and carry them to sell to summer residents.

Summer residents, in decorated, architecturally elaborate houses, lazily walk under umbrellas, in light, clean, expensive clothes along sand-strewn paths, or sit in the shade of trees, gazebos, at painted tables and, languishing in the heat, drink tea or soft drinks.

At the magnificent dacha of Nikolai Semenych, with a tower, a veranda, a balcony, galleries - everything is fresh, brand new, clean - there is a troika with bells in a carriage, which brought from the city for fifteen “back and forth”, as the coachman says, a St. Petersburg gentleman.

This gentleman is a well-known liberal figure who participated in all committees, commissions, offerings, cunningly composed, as if loyal, but in essence the most liberal addresses. He came from the city, in which he, as always, a terribly busy man, would only stay for a day, to his friend, childhood comrade and almost like-minded person.

They only differ slightly in the way they apply constitutional principles. A Petersburger is more of a European, with little partiality even for socialism, and receives a very large salary for the positions he occupies. Nikolai Semenych is a purely Russian man, Orthodox, with a touch of Slavophilism, and owns many thousands of acres of land.

They dined in the garden with a five-course meal, but because of the heat they ate almost nothing, so the efforts of the forty-ruble cook and his assistants, who worked especially hard for the guest, were almost in vain. We only ate iced botvinya with fresh whitefish and multi-colored ice cream in a beautiful shape and decorated with various sugar hairs and biscuits. Dining was a guest, a liberal doctor, the children's teacher - a student, a desperate Social Democrat, a revolutionary, whom Nikolai Semenych knew how to keep in check, Marie - the wife of Nikolai Semenych, and three children, the youngest of whom only came to the cake.

The dinner was a little tense, because Marie, herself a very nervous woman, was preoccupied with Goga’s stomach upset—that’s how the younger boy Nikolai was called (as usual among decent people)—and also because, as soon as the political conversation began between the guest and Nikolai Semenych, a desperate student, wanting to show that he was not embarrassed to express his convictions to anyone, burst into the conversation, and the guest fell silent, while Nikolai Semenych calmed the revolutionary down.

We had lunch at seven o'clock. After lunch, the friends sat on the veranda, cooling off with cold Narzan and light white wine, and talked.

Their disagreement was primarily expressed in the question of whether there should be two-degree or one-stage elections, and they began to argue heatedly when they were called to tea in the dining room, protected by fly nets. Over tea there was a general conversation with Marie, who could not be interested in this conversation, since she was completely absorbed in the thought of Goga’s signs of indigestion. The conversation was about painting, and Marie argued that in decadent painting there is an un je ne sais quoi that cannot be denied. At that moment she was not thinking at all about decadent painting, but she said what she had said many times. The guest no longer needed this at all, but he had heard what was said against decadence, and he said it all so similarly that no one would have guessed that he had nothing to do with decadence or non-decadence. Nikolai Semyonitch, looking at his wife, felt that she was dissatisfied with something and that there would probably be some kind of trouble - besides, he was very bored listening to what she said and what he heard, it seemed to him, was more than a hundred times.

They lit expensive bronze lamps and lanterns in the courtyard, put the children to bed, and subjected the sick Goga to medical operations.

The guest with Nikolai Semenych and the doctor went out onto the veranda. The footman brought candles with caps and more to the narzan, and at about twelve o'clock a real, lively conversation began about what government measures should have been taken at this important time for Russia. Both smoked continuously and talked.

Outside, outside the gates of the dacha, the coachmen's horses, standing without food, rattled their bells, and the old coachman, who was sitting in a carriage for twenty years and lived with all his salary, with the exception of three or five rubles, which he drank away, also yawned and snored, also without food. , who sent it home to his brother. When the roosters from different dachas began to call to each other, and especially one loud, thin one in the neighboring dacha, the driver doubted whether he had been forgotten, got off the carriage and entered the dacha. He saw that his rider was sitting and drinking something and talking loudly in between. He became afraid and went to look for the footman. A footman in a livery jacket was sitting and sleeping in the hallway. The coachman woke him up. A footman, a former servant, who supported his large family - five girls and two boys - with his service (the service was profitable - fifteen rubles in salary and from the gentlemen in a tip a year, sometimes up to a hundred) - jumped up and, having recovered and dusted himself off, went to the gentlemen to say, that the driver is worried and asks to be let go.

When the footman entered, the argument was in full swing. The doctor who approached them took part in it.

“I cannot allow,” said the guest, “that the Russian people should follow some other path of development.” First of all, we need freedom - political freedom - that freedom, as everyone knows, is the greatest freedom, while respecting the greatest rights of other people.

The guest felt that he was confused and was saying something wrong, but in the heat of the argument he could not properly remember how to speak.

“That’s true,” answered Nikolai Semenych, not listening to the guest and only wanting to express his thought, which he especially liked. - This is true, but this is achieved in a different way - not by a majority vote, but by universal consent. Look at the world's decisions.

- Oh, this world.

“It cannot be denied,” said the doctor, “that the Slavic peoples have their own special view.” For example, the Polish right of veto. I'm not saying this is better.

“Allow me to finish my whole thought,” Nikolai Semenych began. — The Russian people have special properties. These properties...

But Ivan, who came with sleepy eyes in his livery, interrupted him:

- The driver is worried...

- Tell him (the St. Petersburg guest said “you” to all the lackeys and was proud of it) that I will go soon. And I'll pay for the extra.

- I’m listening, sir.

Ivan left, and Nikolai Semenych could finish his whole thought. But both the guest and the doctor heard it twenty times (or at least it seemed so to them) and began to refute it, especially the guest, with examples of history. He knew history very well.

The doctor was on the guest's side and admired his erudition and was glad to have the opportunity to meet him.

The conversation dragged on so long that it became light beyond the forest on the other side of the road and the nightingale woke up, but the interlocutors kept smoking and talking, talking and smoking.

Perhaps the conversation would have continued, but the maid came out of the door.

This maid was an orphan who, in order to feed herself, had to enter service. At first she lived with merchants, where the clerk seduced her and she gave birth. Her child died, she went to work with an official, where her son, a high school student, did not give her peace, then she became an assistant maid to Nikolai Semyonovich and considered herself happy that the masters were no longer persecuting her with their lust and paid her a regular salary. She came in to report that the lady’s name was the doctor and Nikolai Semyonitch.

“Well,” thought Nikolai Semenych, “surely there’s something wrong with Goga.”

- And what? - he asked.

“Nikolai Nikolaevich is somehow unwell,” said the maid. Nikolai Nikolaevich, “they” - this was Goga, overcome by diarrhea and overeating.

“Well, it’s time,” said the guest, “look how light it is.” “We’ve been sitting too long,” he said, smiling, as if praising himself and his interlocutors for talking so long and so much, and said goodbye.

Ivan ran for a long time with tired legs to retrieve the guest’s hat and umbrella, which the guest himself had put in the most inappropriate places. Ivan hoped to receive a tip, but the guest, always generous and would not have regretted giving him a ruble, carried away by the conversation, completely forgot about it and only remembered on the way that he had not given anything to the footman. “Well, there’s nothing to do.”

The coachman climbed onto the box, picked up the reins, sat sideways and set off. The bells were ringing. The Petersburger, swaying on soft springs, rode and thought about the limitations and bias of his friend’s thoughts.

Nikolai Semenych thought the same thing, he did not immediately go to his wife. “This St. Petersburg narrow-mindedness is terrible. They can’t get out of this,” he thought.

He hesitated to go to his wife, because now he did not expect anything good from this meeting. It was all about the berries. The boys brought berries yesterday. Nikolai Semenych bought, without haggling, two plates of not quite ripe berries. The children came running, begging for themselves, and began to eat directly from the plates. Marie hasn't left yet. And when she came out and found out that Goga had been given berries, she became terribly angry, since his stomach was already upset. She began to reproach her husband, and he reproached her. And an unpleasant conversation ensued, almost a quarrel. By evening, for sure, Goga was not feeling well. Nikolai Semenych thought that this would end, but the doctor’s call meant that things had taken a bad turn.

When he came to his wife, she, in a colorful silk robe, which she really liked, but which she now did not think about, was standing in the nursery with the doctor over the potty and shining a flowing candle there for him.

The doctor with an attentive look, wearing pince-nez, looked there, stirring the stinking contents with his wand.

“Yes,” he said significantly.

- All these damn berries.

“Well, why the berries,” Nikolai Semenych said timidly.

- Why berries? You fed him, but I don’t sleep at night, and the child will die...

“Well, he won’t die,” the doctor said, smiling, “with a little bismuth and caution.” Let's give it now.

“He fell asleep,” said Marie.

- Well, it’s better not to disturb, I’ll come by tomorrow.

- Please.

The doctor left, Nikolai Semenych was left alone and for a long time could not calm his wife down. When he fell asleep, it was already quite light.

In the neighboring village at that very time, men and boys were returning from a night out. Some were on one, some had horses in the lead, and swifts and two-year-olds were running behind them.

Taraska Rezunov, a boy of about twelve, in a short fur coat, but barefoot, in a cap, on a piebald mare with a gelding in the reins and a piebald groom like his mother, overtook everyone and galloped up the hill to the village. The black dog ran merrily ahead of the horses, looking back at them. The piebald, well-fed shearer from behind kicked his white legs in stockings first in one direction and then in the other. Taraska rode up to the hut, got down, tied the horses at the gate and entered the hallway.

- Hey, you fell asleep! - he shouted at his sisters and brother, who were sleeping in the hallway on a sackcloth.

The mother, who was sleeping next to them, had already gotten up to milk the cow.

Olga jumped up, straightening her tousled long whitish hair with both hands, while Fedka, who was sleeping with her, was still lying with his head buried in his fur coat, and was only rubbing his calloused heel on a slender child’s leg sticking out from under his caftan.

The guys had been going out to pick berries since the evening, and Taraska promised to wake up his sister and little one as soon as he returned from his night out.

He did just that. At night, sitting under a bush, he fell from sleep; Now he was having a blast and decided not to go to bed, but to go with the girls to pick berries. His mother gave him a mug of milk. He cut himself a slice of bread and sat down at the table on a high bench and began to eat.

When he, in only a shirt and trousers, with quick steps, making clear traces of bare feet in the dust, walked along the road along which there were already several of the same, some larger, others smaller, barefoot footprints with clearly imprinted toes, the girls were already visible in red and white spots far ahead in the dark green of the grove. (In the evening they prepared themselves a pot and a mug and, without having breakfast or stocking up on bread, crossed themselves twice at the front corner and ran into the street.) Taraska caught up with them behind a large forest, just as they turned off the road.

Dew lay on the grass, on the bushes, even on the lower branches of bushes and trees, and the girls’ bare legs immediately became wet and first became cold, and then warmed up, stepping first on the soft grass, then on the unevenness of the dry earth. The berry place was in a cleared forest. The girls first entered last year's clearing. The young shoots were just rising, and between the lush young bushes there were places with short grass, in which pinkish-white and here and there red berries were ripening and hiding.

The girls, bent double, picked out berry after berry with their little tanned hands and put the worst ones in their mouths, the better ones in a mug.

- Olgushka! come here. There's a lot here.

- Well? Wrong! Aw! - they called to each other, not far apart when they went behind the bushes.

Taraska went further away from them beyond the ravine in the previous year, a forest had been cut down, on which the young growth, especially walnut and maple, was taller than human height. The grass was juicier and thicker, and when there were places with strawberries, the berries were larger and juicier under the protection of the grass.

- Grushka!

- Ahh!

- How's the wolf?

- Well, what about the wolf? Are you scaring me? “But I’m not afraid,” said Grushka, and, having forgotten herself, she, thinking about the wolf, put berry after berry, and the best ones not in a mug, but in her mouth.

- And our Taraska went beyond the ravine. Taras-ka-a!

- I-oh! - Taraska answered from behind the ravine. - Come here.

- And then let’s go, there’s more there.

And the girls climbed down into the ravine, holding on to the bushes, and from the ravine with screwdrivers to the other side, and then, in the rays of the sun, they immediately attacked a clearing with fine grass, completely strewn with berries. Both were silent and did not stop working with their hands and lips.

Suddenly something shook and, in the midst of the silence, with what seemed to them a terrible roar, it crackled through the grass and bushes.

The pear fell from fear and scattered the collected berries halfway through the mug.

- Mommy! - she squealed and began to cry.

- It's a hare, a hare! Taraska! Hare. “There he is,” Olgushka shouted, pointing to a gray-brown back with ears flashing between the bushes. - What are you doing? - Olgushka turned to Grushka when the hare disappeared.

“I thought it was a wolf,” answered Grushka, and suddenly, immediately after the horror and tears of despair, she burst out laughing.

- What a fool.

- Passion got scared! - said Grushka, bursting into bell-like laughter.

We picked up the berries and moved on. The sun had already risen and brightened the greenery with bright spots and shadows and shone in the drops of dew, in which the girls were now wet to their waists.

The girls were already almost at the end of the forest, going further and further, in the hope that as they went further there would be more berries, when in different places they heard the ringing hootings of girls and women who came out later and were also picking berries.

At breakfast, the mug and pot were already half full when the girls met Aunt Akulina, who had also gone out to pick berries. Behind Aunt Akulina, a tiny, pot-bellied boy in only a shirt and no hat hobbled on thick crooked legs.

“He stuck with me,” Akulina said to the girls, taking the boy in her arms. - And there is no one to leave with.

- And now we scared away a healthy hare. The sound of it cracking is terrible...

- Look! - said Akulina and again let go of the little one.

After talking like this, the girls parted ways with Akulina and continued their work.

“You know, let’s sit for a while,” Olgushka said, sitting down under the thick shade of a walnut bush. - I'm exhausted. Eh, they didn’t take the bread, I wish I could eat now.

“And I want to,” said Grushka.

- Why is Aunt Akulina screaming something painful? Can you hear it? Hey, Aunt Akulina!

- Olgushka! - Akulina responded.

- Chago!

- Is your little one not with you? - Akulina shouted from behind the screwdriver.

- No.

But then the bushes rustled, and Aunt Akulina herself appeared from behind the screwdriver with her skirt picked up above her knees and a purse on her hand.

— Haven’t you seen anything?

- No.

- What a sin! Teddy bear!

- Bear!

Nobody responded.

- Oh, my dear, he will get lost. He wanders into a big forest.

Olgushka jumped up and went with Grushka to look in one direction, Aunt Akulina in the other. They kept calling for Mishka in loud voices, but no one responded.

“I’m exhausted,” said Grushka, falling behind, but Olgushka kept yowling and walked first to the right, then to the left, looking around.

Akulina's desperate voice was heard far away towards the large forest. Olgushka was about to give up searching and go home, when in one succulent bush, near the stump of a young linden tree, she heard the persistent and angry, desperate squeak of some bird, probably with chicks, dissatisfied with something. The bird was obviously afraid of something and was angry about something. Olgushka looked back at the bush, overgrown with thick, tall grass with white flowers, and right under it she saw a blue bunch, unlike any forest herbs. She stopped and took a closer look. It was Mishka. And the bird was afraid of him and angry with him.

The bear lay on his thick belly, with his little hands under his head and his plump crooked legs stretched out, and slept sweetly.

Olgushka called her mother and, waking up the little one, gave him some berries.

For a long time afterwards, Olgushka told everyone she met, at home, to her mother, to her father, and to her neighbors, how she searched for and how she found little Akulininov.

The sun had already completely come out from behind the forest and was hotly baking the earth and everything that was on it.

- Olgushka! “To swim,” the girls who got along with her invited Olga. And everyone went to the river in a big round dance, singing. Floundering, squealing and dangling their legs, the girls did not notice how a low black cloud was setting from the west, how the sun began to hide and open, and how it smelled of flowers and birch leaves and began to rumble. Before the girls had time to get dressed, the rain poured down and wet them to the skin.

With their shirts clinging to their bodies and darkened, the girls ran home, ate and took them to the field where their father was plowing potatoes for dinner.

When they returned and had lunch, their shirts were already dry. After sorting out the strawberries and putting them in cups, they took them to Nikolai Semyonovich’s dacha, where they paid well; but this time they were refused.

Marie, sitting under an umbrella in a large chair and languishing from the heat, saw the girls with berries and waved her fan at them.

- No need, no need.

But Valya, the eldest, a twelve-year-old boy, taking a break from the overwork of the classical gymnasium and playing croquet with his neighbors, saw the berries, ran up to Olgushka and asked:

- How many?

She said:

- Thirty kopecks.

“A lot,” he said. He said “a lot” because that’s what the big ones always said. “Wait, just go around the corner,” he said and ran to the nanny.

Olgushka and Grushka, meanwhile, admired the mirror ball, in which some small houses, forests, and gardens could be seen. And this ball and much more was not surprising to them, because they expected all the most wonderful things from the mysterious and incomprehensible world of people-masters.

Valya ran to the nanny and began to ask her for thirty kopecks. The nanny said that twenty would be enough, and took money out of his chest. And he, walking around his father, who had just gotten up after a hard night yesterday, was smoking and reading newspapers, gave two kopecks to the girls and, pouring berries into a plate, attacked them.

Returning home, Olgushka untied with her teeth the knot in the scarf in which the two-kopeck coin was tied, and gave it to her mother. The mother hid the money and collected the laundry for the river.

Taraska, who had been plowing potatoes with his father since breakfast, was sleeping at that time in the shade of a thick dark oak tree, and his father was sitting right there, looking at the tangled harnessed horse, which was grazing on the border of someone else's land and could at any moment go into the oats or someone else's meadows.

Everything in Nikolai Semenych’s family today was as usual. Everything was fine. The three-course breakfast was ready, the flies had been eating it for a long time, but no one came because no one wanted to eat.

Nikolai Semenych was pleased with the fairness of his judgments, which became clear from what he read today in the newspapers. Marie was calm because Goga went well. The doctor was pleased that the remedies he proposed were beneficial. Valya was pleased that he ate a whole plate of strawberries.