It is important for every person to be able to communicate, since such a skill is a good assistant in many life situations. Almost all successes in school, work, and personal life are built on communication skills. If the information is presented by the speaker concisely and structured, then it will reach the listeners in the best possible way. The science that studies all the details of oratory is called rhetoric. It is thanks to her that you can make your speech clear and convincing. Rhetoric – what is it? Science or academic discipline?

What is teaching?

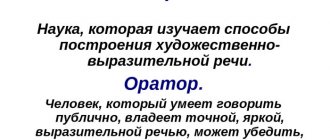

What does the word "rhetoric" mean? Translated from Greek, the word rhetoric looks like “rhetorike” and means “oratory.” Initially, this definition implied the ability to speak beautifully and express one’s thoughts in front of other people.

Over time, the concept of rhetoric changed several times, which was influenced by changing periods of people’s cultural development. Therefore, this science, from antiquity to the present time, was perceived differently.

It was founded by the sophists, who said that rhetoric is a discipline that can teach a speaker to prove his position, manipulate and dominate discussions. In modern times, the basis of such a science is harmonizing speech, the search for truth, and stimulation of thought.

Now the word rhetoric is understood as a discipline that allows you to study methods of forming speech, characterized by expediency, harmony, and the ability to influence. In this regard, the subject of rhetoric acts as a mental-speech action. Rhetoric combines the teachings of philosophy, sociology, and psychology, which helps to achieve effective verbal interaction with any public.

Thus, modern rhetoric is considered from three sides:

- This is a science that examines the art of speech, which has specific standards for public speaking in front of people, allowing one to achieve a good result when influencing listeners.

- This is the highest level of skill in delivering a speech in front of an audience, mastery of words at a professional level and excellent oratory.

- An academic discipline that helps students instill the rules of public speaking.

Thus, general rhetoric studies the rules for constructing expedient and persuasive speech, which helps make the speech vivid and memorable.

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, rhetoric continued to improve in France, Italy and Germany, and religion had a significant influence on it. Thus, by the 5th century, the science of Christian oratory reached extraordinary development, the outstanding representative of which was the Archbishop of Constantinople John Chrysostom. At the same time, medieval rhetoric continues to use the rules developed by ancient orators - ancient developments are only adapted for use in religious messages and sermons. Oratory skills are taught in Christian educational institutions.

What does science study?

The subject of rhetoric, as a science, includes methods of forming useful oral and written speech, as well as the process by which thoughts are transformed into speech.

In order to determine the tasks of rhetoric, it is necessary to know about its main directions. There are two of them:

- Logical, in which the main aspects are the ability to convince the listener and effectively present information.

- Literary, in which the most important elements are the richness and attractiveness of words.

Taking into account the fact that in this science these directions are combined, real rhetoric sets itself the task of making speech correct, convincing and expedient. Having defined what rhetoric is and why it is needed, there is no doubt about its necessity in the life of a person, especially those engaged in public activities.

Fundamentals of Rhetoric

Rhetoric will tell you everything about public speech, its stages, goals, sources of material, methods of presentation, means of speech influence, as well as the requirements for the speaker’s personality.

Today, the ability to competently build communication is a necessary condition for success in the social life of every person. For those who are directly involved in speaking in front of an audience, this skill is the key to professional excellence.

Let's find out what an effective public speech should be.

The speaker’s speech will be successful if it organically combines logic and emotionality, information content and expressiveness. It is good if it is not read, but pronounced in the form of live communication with listeners.

Rhetoric in ancient times

The origin of rhetoric began in ancient Greece. Due to the fact that democracy was being formed in this state, the ability to persuade gained considerable popularity in society.

Every resident of the city had the opportunity to undergo training in oratory, which was taught by the sophists. These sages considered rhetoric to be the science of persuasion, which studies ways of verbally defeating an opponent. Because of this, the word “sophism” subsequently caused a negative reaction. After all, under them, rhetoric was considered as a trick, an invention, but earlier this science was considered the highest skill, skill.

In Ancient Greece, many works were created that revealed rhetoric. Who is the author of the classic Greek treatise on this science? This is the well-known thinker Aristotle. This work, called “Rhetoric,” distinguished oratory from all other sciences. It defined the principles on which speech should be based and indicated the methods used as evidence. Thanks to this treatise, Aristotle became the founder of rhetoric as a science.

In Ancient Rome, Marcus Tullius Cicero, who was involved in politics, philosophy and oratory, contributed to the development of rhetoric. He created a work called "Brutus or on the Famous Orators", describing the development of science in the names of popular speakers. He also wrote a work “On the Speaker,” in which he talked about what kind of speech behavior a worthy speaker should have. Then he created the book “Orator”, revealing the basics of eloquence.

Cicero considered rhetoric the most complex science, unlike others. He argued that in order to become a worthy speaker, a person must have deep knowledge in all areas of life. Otherwise, he simply will not be able to maintain a dialogue with another person.

The meaning of the word rhetoric

(ρητορική τέχνη) - in the original meaning of the word - the science of oratory, but later it was sometimes understood more broadly, as a general theory of prose. European eloquence got its start in Greece, in the schools of sophists, whose main task was purely practical training in eloquence; therefore, their R. contained many rules related to stylistics and grammar itself. According to Diogenes Laertius, Aristotle attributed the invention of R. to the Pythagorean Empedocles, whose work is unknown to us even by name. From the words of Aristotle himself and from other sources, we know that the first treatise on R. belonged to Empedocles’ student, Corax, a favorite of the Syracusan tyrant Hiero, a political orator and lawyer. In him we find an interesting definition: “eloquence is the worker of persuasion (πειθοΰς δημιουργός)”; he is the first to attempt to establish the division of oratorical speech into parts: introduction (προοιμιον), proposal (κατάστάσις), presentation (διήγησις), proof or struggle (άγών), fall (παρέκβασις) and conclusion; He also put forward the position that the main goal of the speaker is not the revelation of the truth, but persuasiveness with the help of the probable (είκός), for which all sorts of sophisms are extremely useful. The work of Corax has not reached us, but ancient writers tell us examples of his sophisms, of which the so-called crocodile enjoyed particular fame. Corax's student, Tizius, developed the same system of sophistic proofs and considered the main means of teaching R. to be memorizing exemplary speeches of judicial orators. From his school came Gorgias of Leontius, who was famous in his time, who, according to Plato, “discovered that the probable is more important than the true, and was able in his speeches to present the small as great, and the great as small, to pass off the old as new and recognize the new as old, about one and the same.” express conflicting opinions on the same subject.” Gorgias' teaching method also consisted of studying patterns; each of his students had to know excerpts from the works of the best speakers in order to be able to answer the most frequently raised objections. Gorgias wrote a curious treatise “on a decent occasion” (περί τοΰ καιροΰ), which spoke about the dependence of speech on the subject, on the subjective properties of the speaker and the audience, and gave instructions on how to destroy serious arguments with the help of ridicule and, conversely, to respond to ridicule with dignity . Gorgias contrasted beautiful speaking (εύέπεια) with the affirmation of truth (όρθοέπεια). He contributed a lot to the creation of rules about metaphors, figures, alliteration, and parallelism of parts of a phrase. Many famous rhetoricians came from the school of Gorgias: Paul of Agrigentum, Licymnius, Thrasymachus, Even, Theodore of Byzantium; The sophists Protagoras and Prodicus and the famous orator Isocrates, who developed the doctrine of the period, belonged to the same stylistic trend. The direction of this school can be called practical, although it prepared rich psychological material for the development of general theoretical principles about the art of oratory and this made the task easier for Aristotle, who in his famous “Rhetoric” (translation by NH Platonova, St. Petersburg, 1894) provides a scientific justification for the previous dogmatic rules using purely empirical methods. Aristotle significantly expanded the field of R., compared with the common view of it at that time. “Since the gift of speech,” he says, “has a universal character and is used in a wide variety of cases, and since the action when giving advice, with all kinds of explanations and persuasion given for one person or for entire assemblies (with which the speaker deals ), essentially the same, then R., just as little as dialectics, deals with any one specific area: it embraces all spheres of human life. Rhetoric, understood in this sense, is used by everyone at every step; it is equally necessary both in matters concerning the everyday needs of an individual and in matters of national importance: once a person begins to persuade another person to do something or dissuade him from something, he must resort to the help of R., consciously or unconsciously.” . Understanding R. in this way, Aristotle defines it as the ability to find possible ways of persuasion regarding each given subject. Hence, the goal that Aristotle pursued in his treatise is clear: he wanted, on the basis of observation, to give general forms of oratory, to indicate what should guide the speaker or, in general, anyone who wants to convince someone of anything. Accordingly, he divided his treatise into three parts: the first of them is devoted to the analysis of those principles on the basis of which an orator (that is, anyone speaking about something) can encourage his listeners to do something or deviate them from something. anything, can praise or blame something. The second part talks about those personal properties and characteristics of the speaker, with the help of which he can inspire confidence in his listeners and thus more accurately achieve his goal, that is, persuade or dissuade them. The third part concerns the special, technical, so to speak, side of rhetoric: Aristotle speaks here about those methods of expression that should be used in speech, and about the construction of speech. Thanks to many subtle psychological comments on the interaction of the speaker and the environment (for example, on the meaning of humor, pathos, on the influence on young people and on old people), thanks to an excellent analysis of the power of evidence used in speech, Aristotle’s work has not lost its significance for our time and had a strong influence on the entire subsequent development of European R.: in essence, some of the questions posed by Aristotle could now be the subject of scientific research, and, of course, the same empirical method that Aristotle used should be used. Having accepted many of Aristotle's provisions as dogmatic truths, R., however - both in Greece and, later, in Western Europe - greatly deviated precisely from his method of research, returning to the path of practical instructions along which the sophists followed. Among the Greeks, after Aristotle, we see two directions: the Attic, which was concerned primarily with the accuracy of expression, and the Asian, which set the goal of entertaining presentation and developed a special high style based on contrasts, replete with comparisons and metaphors. In Rome, the first follower of this Asian trend was Hortensius, and subsequently Cicero joined him, speaking, however, in some works in favor of Atticism, the most elegant representative of which in Roman literature can be considered Caesar. Already at this time one can see in the works of some rhetoricians the emergence of the theory of three styles - high, middle and low - developed in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Cicero owns a considerable number of treatises on oratory (for example, Brutus, Orator), and Roman R. received its most complete expression in the works of Quintilian; she was never distinguished by originality. In the era of the struggle of Christianity with ancient paganism, the science of Christian oratory was created (see Homiletics), which reached brilliant development in the 4th and 5th centuries. after R.H. In a theoretical sense, it adds almost nothing to what was developed by antiquity. In Byzantium, R.'s techniques come closest to the Asian direction, and in this form this science was transmitted to ancient Rus', where we can see excellent examples of its influence in the works of Metropolitan Hilarion and Cyril of Turov. In the West, R. adheres to the instructions of Aristotle, Cicero and Quintilian, and these instructions turn into indisputable rules, and science becomes some kind of legislative code. This character is asserted in European R., especially in Italy, where, thanks to the meeting of the Latin scientific and Italian folk languages, the theory of three styles is best applied. In the history of Italian R., Bembo and Castiglione occupy a prominent place as stylists, and the legislative direction is especially clearly expressed in the activities of the Academy della Crusca, whose task is to preserve the purity of the language. In the works of, for example, Sperone Speroni, there is a noticeable imitation of Gorgias’s techniques in antitheses, the rhythmic structure of speech, and the selection of consonances, and in the Florentine Davanzati a revival of Atticism is noticed. From Italy this direction is transferred to France and other European countries. A new classicism is being created in R., which finds its best expression in Fenelon’s Discourse on Eloquence. Every speech, according to Fenelon’s theory, should either prove (ordinary style), or depict (medium), or captivate (high). According to Cicero, the oratorical word should approach the poetic; there is no need, however, to pile up artificial decorations. We must try to imitate the ancients in everything; the main thing is clarity and correspondence of speech to feelings and thoughts. Interesting data for characterizing French R. can also be found in the history of the French Academy and other institutions that protected traditional rules. The development of R. in England and Germany throughout the 18th century was similar. In our century, the development of political and other types of eloquence should have led to the abolition of the conventional, legislative rules of oratory - and R. returns to the path of observation outlined by Aristotle. The concept of science is also expanding: thus, in Wackernagel, R. contains the entire theory of prose and is divided into two sections (narrative and instructive prose), and comments on style are completely excluded from R., since they apply equally to poetry and to prose, and therefore constitute a special department of stylistics. In Russia, in the pre-Petrine period of the development of literature, R. could only be used in the field of spiritual eloquence, and the number of its monuments is absolutely insignificant: we have some stylistic remarks in Svyatoslav’s “Izbornik”, a curious treatise of the 16th century: “The Speech of Greek Subtlety” ( ed. Society of Lovers of Ancient Writing) and “The Science of Composing Sermons”, Ioannikiy Golyatovsky. The systematic teaching of R. began in southwestern theological schools in the 17th century, and the textbooks were always Latin, so there is no need to look for an original treatment in them. The first serious Russian work is Lomonosov's Rhetoric, compiled on the basis of classical authors and Western European manuals and providing a number of examples in Russian in support of general provisions - examples drawn partly from the works of new European writers. Lomonosov, in his “Discourse on the Use of Church Books,” applies the Western theory of three styles to the Russian language. Due to the fact that the field of eloquence in Russia was limited almost exclusively to church sermons, R. almost always coincides with homiletics (see); on secular rhetoric we have extremely few works, and even those are not distinguished by their independence, like, for example, the leadership of Koshansky (see). The scientific development of R. in the sense as it is understood in the West has not yet begun in our country.

Wed. Chaignet, "La rhetorique et son histoire"; Egger, “Histoire de la critique chez les anciens Grecs”; Wackernagel, "Poetik, Rhetorik und Stilistik"; Philippi, "Die Kunst der Rede"; Sumtsov, “Ioanniky Golyatovsky”; Pekarsky, “History of the Academy of Sciences”; Sukhomlinov, “History of the Russian Academy.”

A. Borozdin.

Development of rhetoric in Russia

Rhetoric in Russia arose on the basis of Roman science. Unfortunately, it was not always in such demand. Over time, when political and social regimes changed, the need for it was perceived differently.

Development of Russian rhetoric in stages:

- Ancient Rus' (XII–XVII centuries). During this period, the term “rhetoric” and educational books on it did not yet exist. But some of its rules were already applied. People at that time called the ethics of speech eloquence, piety or rhetoric. Teaching the art of the word was carried out on the basis of liturgical texts created by preachers. For example, one of these collections is “The Bee,” written in the 13th century.

- First half of the 17th century. During this period, a characteristic event was that the first Russian textbook was published, revealing the basics of rhetoric.

- The end of the 17th – the beginning and middle of the 18th century. At this stage, the book “Rhetoric”, written by Mikhail Usachev, was published. Many works were also created, such as “Old Believer Rhetoric”, works “Poetics”, “Ethics”, several lectures on the rhetorical art of Feofan Prokopovich.

- XVIII century. At this time, the formation of rhetoric as a Russian science took place, to which Mikhail Vasilyevich Lomonosov made a huge contribution. He wrote several works dedicated to it, of which the book “Rhetoric” became the basis for the development of this science.

- Beginning and mid-19th century. This period is characterized by the fact that there was a rhetorical boom in the country. Famous authors published a large number of textbooks. These include the works of I.S. Rizhsky, N.F. Koshansky, A.F. Merzlyakova, A.I. Galich, K.P. Zelensky, M.M. Speransky.

However, starting from the second half of the century, this science begins to actively supplant literature. Soviet people studied stylistics, linguistics, speech culture, and criticized rhetoric.

Laws of word art

Rhetoric at any time had its ultimate goal - to influence listeners. A special role in achieving this is played by expressive speech, as well as visual and expressive means.

Scientists divide this science into two types - general and particular. The subject of general rhetoric includes general methods of behavior when pronouncing speech and the practical possibilities of their application in order to make speech effective.

This variety includes the following sections:

- rhetorical canon;

- speaking in front of an audience;

- rules on how to argue;

- conversation norms;

- teachings about everyday communication;

- communication between different nations.

By studying these sections, the speaker gains knowledge about the main features of speech use, which are the basis for every master of words.

General rhetoric studies ways to achieve mutual understanding between the speaker and the audience. For this purpose the following laws were developed:

- The law of harmonizing dialogue. The speaker must awaken the feelings and thoughts of the listeners, turning the monologue into a dialogue. It is possible to build harmonious communication only through dialogue between all people participating in the discussion. The essence of this rule is more accurately revealed by the following laws.

- The law of listener orientation and advancement. The person at whom the orator's influence is directed should have the feeling as if he, together with the speaker, is moving towards the intended goal. To achieve this effect, the speaker must use words in speech that determine the order of events, connect sentences and summarize expressions.

- The law of emotional speech. A person speaking in front of an audience must himself experience the feelings that he is trying to evoke in the audience, and also be able to convey them through speech.

- Law of pleasure. It implies the ability to present speech in such a way that it brings pleasure to listeners. This effect is easy to achieve if the speech is expressive and rich.

A particular type of rhetoric is based on a general type and involves the specific use of general provisions in certain areas of life. Thus, science studies what rules of speech pronunciation and behavior a speaker needs to apply depending on the situation.

There are a lot of private rhetorics, but they all fall into two main groups:

- Homiletics.

- Oratory.

The first group implies the speaker’s ability to repeatedly influence the audience. This includes church and academic types of eloquence. In modern rhetoric, this group includes propaganda that is carried out in the media.

Thus, with academic eloquence, a speaker, giving several lectures, should not speak anew each time about the purposes of their conduct, their necessity, and so on. It is enough for him to talk about this in the first lecture, and in all the rest the general task will be expanded through the study of a new topic.

Oratory is not capable of influencing people many times over. In this regard, the speaker must be able to correctly conclude each speech. This group includes judicial, everyday, socio-political and other types of eloquence.

Currently, oratory has grown quite widely, so a specific type of rhetoric has already begun to be divided into its own subspecies. For example, administrative, diplomatic, parliamentary and other rhetoric were distinguished from socio-political eloquence.

Test with answers: “Rhetoric”

1. What is legal deontology? a) the doctrine of problems of morality and morality in legal activity; + b) the doctrine of the preparation of judicial speech; c) teaching about the problems of drafting texts for legal proceedings; d) the doctrine of new techniques of eloquence in legal practice.

2. At the end of his speech, the speaker is not allowed to: a) Bow, bow b) Apologize, make excuses + c) Applaud, thank you for listening

3. What is the name for the use of words, phrases and expressions with multiple meanings? a) Paths + b) Fetters c) Masses

4. Author of the first treatise on the basics of rhetoric: a) Tisias b) Plato c) Corax+

5. This state proclaimed rhetoric the queen of sciences: a) Greece + b) Italy c) Egypt

6. Read the sentences and determine the type of error: “Personally, I have nothing against your understanding of this issue.” Answer: pleonasm

7. What does it mean when a speaker begins a speech (lecture, report) with an apology to the audience? Answer: the speaker does not know how to use audience feedback

8. Where does the preparation of a judicial speech begin? a) with the logical organization of the material; b) from determining the topic of speech and target setting; c) from the selection of arguments and evidence; d) from studying the materials of the (civil, criminal) case. +

9. Read the sentences and determine the type of error: “I will go to Chechnya, and the date is already known. This will be in January 1998” (From an interview with President B.N. Yeltsin on TV in December 1997) Answer: pleonasm

10. Read the sentences and determine the type of error: “They pay a lot of attention to this parable...” (From a TV program on December 6, 1987 about A. Parker’s film “Angel Heart” 1987) Answer: contamination

11. What is a metaphor? a) a trope, a word or expression used in a figurative meaning, which is based on an unnamed comparison of an object with any other on the basis of their common characteristic; + b) trope, which consists in using a name (or an entire statement) in a sense that is directly opposite to the literal one; transfer - by contrast, by polarity of semantics; c) a figure of speech based on a comparison of two phenomena, objects that are assumed to have a common characteristic; d) a stylistic device consisting of two or more units arranged in increasing intensity of action or quality.

12. What should be the speaker’s posture and gestures during a speech? a) the speaker should stand in front of the audience without leaning on a table or chair b) the most expressive parts of speech can be emphasized by moving one leg forward c) both answers are correct +

13. Read the sentences and determine the type of error: “Today we congratulate the graduate of the Department of Management of Foreign Economic Relations and Marketing on the successful completion of his studies” (from the opponent’s speech after defending his diploma) Answer: failure to distinguish between paronyms

14. Which of the authors considered the main argument that one should speak clearly and accurately? a) Cicero + b) Socrates c) Lysias

15. Complete the definition: Rhetoric is the science of searching for truth... a) generalizing the concept of reality b) the construction and structure of speech + c) the special meaning of words in the life of society

Varieties of speaker speech

There are several types of oratory, depending on who needs to be convinced, where the speech takes place, and what purpose it pursues. These include the following eloquences:

- Social and political. This is when they read reports touching on social, political and economic topics, speak at rallies, and conduct campaigning.

- Academic. This includes reading lectures, scientific reports or communications.

- Judicial. This type of eloquence is used by the prosecutor and defense attorney when speaking in court. With their speech they must convince of the guilt or innocence of the accused person.

- Social and everyday life. It is used by all people when making speeches at anniversaries, feasts or funerals. This also includes small talk, which does not require disputes or discussions, but is characterized by ease and simplicity of perception.

- Bogoslovskoe. This eloquence is used in churches, for example, when believers give a sermon or other speech in a cathedral.

- Diplomatic. This type involves compliance with ethical standards in business speech. This is necessary during business negotiations, correspondence, when drawing up official documents, as well as during translation.

- Military. This type of eloquence is used when calling for battle, issuing orders, regulations, and transmitting information via radio communications.

- Pedagogical. This includes presentations by teachers and students, both oral and written. This also includes giving lectures, which is considered a complex act of pedagogical communication.

- Internal, or imaginary. This is the name of the dialogue that every person conducts with himself. This type involves mental preparation for oral presentation to the public, as well as for written transmission of information, when a person reads what is written to himself, remembers something, reflects on something, and so on.

Based on the above, we can conclude what rhetoric is and why society needs it. Rhetoric as the science of oratory involves the study of the correct pronunciation of speech in front of an audience in order to somehow influence the people listening to it. With its help, speakers acquire skills that allow them to make their speech correct, appropriate, and most importantly, convincing.

Types of rhetoric

Currently, there is the following classification of rhetoric by type:

- socio-political (parliamentary and rally speeches, campaign speeches), which is characterized by emotionality, and often pathos, for persuasion and motivation to action;

- academic (scientific review, educational lecture), with arguments and facts, structured, sometimes monotonous and indifferent, as soon as the speaker loses touch with the audience, reading a prepared text;

- social and everyday (welcome, table, anniversary address, toast), for the most part simple and sincere, not distinguished by perfect logic and clear structure, but sincere and kind-hearted;

- judicial (accusatory, defensive), strictly reasoned and balanced, determining the fate of a person;

- theological-church (sermon, official church speech) uplifting spiritually, bringing joy, instructing for good;

- military (address-order, instructive, inspiring speech), specific, strict, strengthening patriotic feelings, nurturing love for the Fatherland;

- diplomatic (speech at international negotiations and conferences), characterized by a high degree of responsibility for every word spoken;

- business (business as well as telephone conversations), the obligatory elements of which are accessibility, expressiveness, and literacy;

- dialogical (interview, argument, discussion), which requires practicing the skills of proper dialogue.